Entering in, and no that's not Elder Mortensen holding hands with Elder Barney

just the camera angle 😟

↑Harrier Jet

There are several scenes around the museum,

this one is a armored track vehicle.

This one is set up for the Viet Nam war, helo's dropping off soldiers in the rice paddies.

This is our group

Recruiting poster for May 1886, a whopping $16 for a PFC per month

In this scene, it was told that this really happened, just a different time than what it shows.

The models we designed after real marines. What is happening is a wounded marine is being tended to in a truck bed, by another marine, not a medic.

Old field cannon

Marine dressed in a gas mask for WWI

Old personal carrier or freight hauler.

I liked it because of the diesel engine.

This one is good, it is a corpsman (again helping a wounded comrade)

Notice the rifle bayonet stuck in the ground with a IV bag hanging from his rifle stock

In WWII the Japanese soldiers used to carry a small flag,

usually signed by family members, or they would write words of encouragement on them.

In this picture⇩ a marine holds a flag, without writing so he decorated it himself, by having his fellow marines sign it, as seen above ⇧notice the picture on the Red Sun, look familiar?

Right, Iwo Jima.

Iwo Jima, ok here's the what and why I wanted these next 4 pictures

This is THE FLAG ( the 2nd flag that is)

From Wikipedia

Two flag-raisings[edit]

There were two American flags raised on top of Mount Suribachi, on February 23, 1945. The photograph Rosenthal took was actually of the second flag-raising in which a larger replacement flag was raised by Marines who did not raise the first flag.

Raising the first flag[edit]

A U.S. flag was first raised atop Mount Suribachi soon after the mountaintop was captured at around 10:20 on February 23, 1945.

Lieutenant Colonel Chandler Johnson, commander of the 2nd Battalion, 28th Marine Regiment, 5th Marine Division, ordered Marine Captain Dave Severance, commander of Easy Company, 2nd Battalion, 28th Marines, to send a platoon to seize and occupy the crest of Mount Suribachi.[9] First Lieutenant Harold G. Schrier, executive officer of Easy Company, who had replaced the wounded Third Platoon commander, John Keith Wells,[10]volunteered to lead a 40-man combat patrol up the mountain. Lieutenant Colonel Johnson (or 1st Lieutenant George G. Wells, the battalion adjutant, whose job it was to carry the flag) had taken the 54-by-28-inch/140-by-71-centimeter flag from the battalion's transport ship, USS Missoula, and handed the flag to Schrier.[11][12] Johnson said to Schrier, "If you get to the top, put it up." Schrier assembled the patrol at 8 AM to begin the climb up the mountain.

Despite the large numbers of Japanese troops in the immediate vicinity, Schrier's patrol made it to the rim of the crater at about 10:15 am, having come under little or no enemy fire, as the Japanese were being bombarded at the time.[13] The flag was attached by Schrier and two Marines to a Japanese iron water pipe found on top, and the flagstaff was raised and planted by Schrier, assisted by Platoon Sergeant Ernest Thomas and Sergeant Oliver Hansen at about 10:30 am[8] (on February 25, during a CBS press interview aboard the flagship USS Eldorado about the flag-raising, Thomas stated that he, Schrier, and Hansen (platoon guide) had actually raised the flag).[14] The raising of the national colors immediately caused a loud cheering reaction from the Marines, sailors, and coast guardsmen on the beach below and from the men on the ships near the beach. The loud noise made by the servicemen and blasts of the ship horns alerted the Japanese, who up to this point had stayed in their cave bunkers. Schrier and his men near the flagstaff then came under fire from Japanese troops, but the Marines quickly eliminated the threat.[citation needed] Schrier was later awarded the Navy Cross for volunteering to take the patrol up Mount Suribachi and raising the American flag, and a Silver Star Medal for a heroic action in March while in command of D Company, 2/28 Marines on Iwo Jima.

Photographs of the first flag flown on Mount Suribachi were taken by Staff Sergeant Louis R. Lowery of Leatherneck magazine, who accompanied the patrol up the mountain, and other photographers.[15][16] Others involved with the first flag-raising include Corporal Charles W. Lindberg, Privates First Class James Michels and Raymond Jacobs, Private Phil Ward, and Navy corpsman John Bradley[17][18] This flag was too small, however, to be easily seen from the northern side of Mount Suribachi, where heavy fighting would go on for several more days.

Raising the second flag[edit]

The photograph taken by Rosenthal was the second flag-raising on top of Mount Suribachi, on February 23, 1945.

On orders from Colonel Chandler Johnson—passed on by Easy Company's commander, Captain Dave Severance—Sergeant Michael Strank, one of Second Platoon's squad leaders, was to take three members of his rifle squad (Corporal Harlon H. Block and Privates First Class Franklin R. Sousley and Ira H. Hayes) and climb up Mount Suribachi to raise a replacement flag on top; the three took supplies or laid telephone wire on the way up to the top. Severance also dispatched Private First Class Rene A. Gagnon, the battalion runner (messenger) for Easy Company, to the command post for fresh SCR-300 walkie-talkie batteries to take to the top.[22]

Meanwhile, Lieutenant Albert Theodore Tuttle[21] under Johnson's orders, had found a large (96-by-56–inch) flag in nearby Tank Landing Ship USS LST-779. He made his way back to the command post and gave it to Johnson. Johnson, in turn, gave it to Rene Gagnon, with orders to take it up to Schrier on Mount Suribachi and raise it.[23] The official Marine Corps history of the event is that Tuttle received the flag from Navy Ensign Alan Wood of USS LST-779, who in turn had received the flag from a supply depot in Pearl Harbor.[24][25][26] Severance had confirmed that the second larger flag was in fact provided by Alan Wood even though Wood could not recognize any of the pictures of the 2nd flag raisers as Gagnon.[27] The flag was sewn by Mabel Sauvageau, a worker at the "flag loft" of the Mare Island Naval Shipyard.[28]

First Lieutenant George Greeley Wells, who had been the Second Battalion, 28th Marines adjutant officially in charge of the two American flags flown on Mount Suribachi, stated in the New York Times in 1991, that Lieutenant Colonel Johnson ordered him (Wells) to get the second flag, and that he (Wells) sent Rene Gagnon his battalion runner, to the ships on shore for the flag, and that Gagnon returned with a flag and gave it to him (Wells), and that Gagnon took this flag up Mt. Suribachi with a message for Schrier to raise it and send the other flag down with Gagnon. Wells stated that he received the first flag back from Gagnon and secured it at the Marine headquarters command post. Wells also stated that he had handed the first flag to Lieutenant Schrier to take up Mount Suribachi.[11]

The Coast Guard Historian's Office recognizes the claims made by former U.S. Coast Guardsman Quartermaster Robert Resnick, who served aboard the USS Duval County at Iwo Jima. "Before he died in November 2004, Resnick said Gagnon came aboard LST-758[29] the morning of February 23 looking for a flag.[30] Resnick said he grabbed a flag from a bunting box and asked permission from his ship's commanding officer Lt. Felix Molenda to donate it.[31] Resnick kept quiet about his participation until 2001."[32][33]

Rosenthal's photograph[edit]

Strank with his three Marines, and Gagnon, reached the top of the mountain around noon without being fired upon. Rosenthal, along with Marine photographers Sergeant Bill Genaust (who was killed in action after the flag-raising) and Private First Class Bob Campbell[34] were climbing Suribachi at this time. On the way up, the trio met Lowery, who had photographed the first flag-raising, coming down. They considered turning around, but Lowery told them that the summit was an excellent vantage point from which to take photographs.[35] The three photographers reached the summit as the Marines were attaching the flag to an old Japanese water pipe.

Rosenthal put his Speed Graphic camera on the ground (set to 1/400 sec shutter speed, with the f-stop between 8 and 11 and Agfa film[36][37]) so he could pile rocks to stand on for a better vantage point. In doing so, he nearly missed the shot. The Marines began raising the flag. Realizing he was about to miss the action, Rosenthal quickly swung his camera up and snapped the photograph without using the viewfinder.[38] Ten years after the flag-raising, Rosenthal wrote:

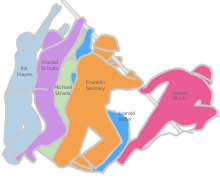

Sergeant Genaust, who was standing almost shoulder-to-shoulder with Rosenthal about three feet away,[37] was shooting motion-picture film during the second flag-raising. His film captures the second event at an almost-identical angle to Rosenthal's shot. Of the six flag-raisers in the picture – Ira Hayes, Harold Schultz (identified in June 2016), Michael Strank, Franklin Sousley, Rene Gagnon, and Harlon Block – only Hayes, Gagnon, and Schultz (Navy corpsman John Bradley was incorrectly identified in the Rosenthal flag-raising photo) survived the battle.[2] Strank and Block were killed on March 1, six days after the flag-raising, Strank by a shell, possibly fired from an offshore American destroyer and Block a few hours later by a mortar round. Sousley was shot and killed by a Japanese sniper on March 21, a few days before the island was declared secure.[39]

There is so much more to tell, for another time.

This picture ⇩ is hard to see, what you are looking at is the wall with a pin for all the Marine/Navy deaths at Iwo Jima. Look closely at the wall, and you see Iwo Jima Island. You can hardly see it standing and looking at it, but the camera lens brings it out.

A Marine dressed as warmly as possible in the Korean War. As the story goes this was the best they had for the time, it was sub-zero temps and everything was frozen. Including the C-rations which was their food. They literally couldn't eat because it was frozen solid.

Here is what "Bing" says about the story:

In November of 1950, the Allied forces were fighting Chinese troops at the Chosin Reservoir in North Korea. American marines fought alongside British troops and South Korean police officers against communist forces. Chairman Mao ordered these troops annihilated and sent 120,000 of his troops to do so.

A cold front moved in, leading to the region’s coldest recorded winter. Everything seemed to be freezing: food rations, fuel lines, their weapons… Some of the men were getting frostbite and the morphine syrettes they were using had to be thawed in a corpsman’s mouth before they could be injected.

The Allied forces used mortar fire to break apart the waves of Chinese soldiers attacking them from the mountain ridges. They quickly ran out of shells and had to call for a resupply in order to keep fighting. The only way they could get the ammunition, however, was by air drop. Commanding officers called in for “tootsie rolls,” their code word for 60mm mortar rounds, but the radio operator on the other end didn’t have a code sheet in front of him. Instead of crucial ammo falling from the sky, tootsie roll candies floated down to the soldiers, shipped from a nearby base in Japan. (bold print added by me).

Although shocked at first, the resilient troops quickly found uses for them. They began warming the candies in their mouths and armpits and using them as a sealant. They mended fuel lines and plugged up bullet holes. The chocolatey goo then froze in the cold air, successfully repairing their equipment. As they marched and fought their way through Korea, they survived by eating the candies. One Veteran, Stanley Kot, explained, “I survived for two weeks on Tootsie Rolls.”

The group, who had taken to calling themselves the Tootsie Roll Marines, suffered 3,000 casualties out of their 15,000 troops. But they eventually made it to the sea, back to safety. Although the candies are small, they truly meant something to those soldiers who fought their way from the Chosin Reservoir. So next time you see a tootsie roll on Halloween, Easter, or at a parade for our military, remember that they’re more than just a candy, they’re a part of our nation’s history.

⇧ A Tootsie Roll wrapper

Another chopper picture.

After we left Quantico, we headed to a church (called Pohick church) which was said to have the oldest baptismal "font" in the US. I used "' because it is not a font as we use, but a "dip your finger in the water and splash on font.

⇧A.D. 1773, I can't argue with that.

Beautiful organ, someone playing while we were there.

The Pulpit

And as usual a church graveyard

We'll see what's next, but until then keep the faith